As part of experiments in visually interpreting The LFTT Library Travel books I have been filming at locations mentioned in the texts under the influence of their historical perspectives. The merging of these first hand accounts from times past (early to mid 1900’s) with my own field based subjectivity results in an other worldly, exotic view tied to genuine encounters with the physical landscape. To provide a critical counterpoint to this stance in the history of cinema I have been researching the work of Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, who generated considerable controversy for his transportation of biblical and archaic narratives into contemporary life.

Films such as; ‘The Gospel According to St. Matthew’ (1964), ‘Oedipus Rex’ (1967) and ‘Notes for an African Orestes’ (1970) reenact mythical stories in present day settings, forming connections across time and place that lend new meaning to both past and present. Pasolini was a self proclaimed catholic, atheist, and marxist. It is the strange combination of opposing values and identities that make his films so compelling, and sometimes difficult to watch.

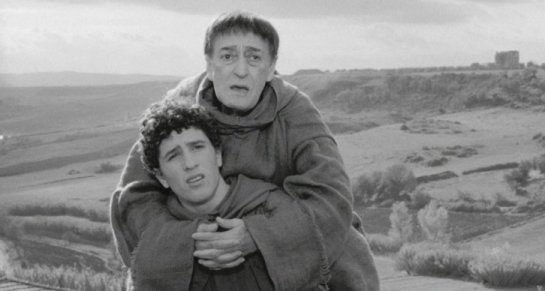

In 1996 Pasolini made a film which could be described as an homage to Saint Francis. ‘The Hawks and The Sparrows’ (1966) (top image, above and below) portrays the journey on foot of two everymen figures, one young one old, with an outspoken crow as a temporary companion. Along the journey the two characters find themselves mythically transported into the past where they meet Saint Francis (On a road that looks just like the present day one but a bit bleaker). Saint Francis pleads with them to help him with his task of teaching religion to the birds. The hawks and the sparrows have been fighting and he hopes the belief in a all-loving God will generate a more neighbourly attitude, but more of that later…

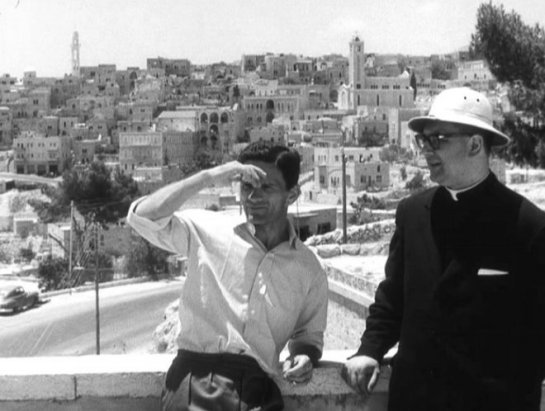

Continuing on our religious Pasolini pilgrimage… ‘Location Hunting in Palestine…’ (1965) (pictured below) is a documentary made by Pasolini of his search for suitable locations to situate the biblical account ‘The Gospel According to St Matthew’ (1964). In ‘Location Hunting…’ we learn how Pasolini is disappointed in his search of the historical sites, finding Israel too industrialised to site the ancient text, while the Arabic communities although suitably ‘archaic’ in their mode of life do not visibly express ‘enlightenment’, as Pasolini puts it something in their expressions appears ‘pre-christian’.

Throughout his career Pasolini has positively courted controversy, and contentious statements made to camera like finding a man turning wheat at the side of the road a ‘vision’ of the ‘archaic’ are no exception. But they raise important issues around the dangers of viewing contemporary cultures through the lens of history, taking history as a linear progression from crude to refined. With statements like these Pasolini is performing a kind of ventriloquism. If crows can talk Pasolini can (fictionally and in reality) be the unpopular voice celebrating preindustrial life. This is suggested by his deliberate use of these self revealing sections in the resulting documentary that allow us to witness his values.

So what has the Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia got to do with any of this? Friuli is the most northeasterly province of Italy bordering Austria and Slovenia and is where I have been staying for the last few weeks. My own reasons for being here are mostly circumstantial; it was the nearest mountainous place to escape the heat within driving distance of Venice (where I had been visiting the Venice Biennale). I had never heard of it before arriving, but was immediately struck by its lush green landscape and dramatic mountain peaks. Parking up in a forest in Clauzetto the first night I had the feeling of being surrounded by prehistory, from the ancient stone bridges and mule tracks crossing the mountain stream to the diversity of growth in the dense woods. Like King Arthur’s ‘Avalon’ everything growing here seemed edible and history and life seemed to perpetuate themselves ad infinitum. There are numerous prehistoric caves in the area of international archaeological importance. (Below ‘Grotte di Pradis’ pic courtesy http://www.summitpost.org)

I was further intrigued to hear the region has its own language – Friulan, which has been proudly guarded since the province maintained autonomy post Italian unification. The ‘San Francesco’ of the previous post is part of this region, as is Tarcento and Gemona where I have also camped (see below and bottom in that order).

So what was my surprise when I find reference to Pasolini’s ‘Friulian’ childhood. As I was reading in Tarcento I learnt he was buried twenty six miles from where I was in Casarsa della Delizia, where there is a center of study devoted to him in his maternal home. After his father was arrested for gambling in 1926 he moved to Casarsa with his mother. At age seven Pasolini wrote his first poem inspired by the beauty of the Friulian landscape. Later on, whilst pursuing a degree in Literature at The University of Bologna, he began to incorporate elements of the Friulian language in his writings.

His first collection of poetry in 1942 was dedicated to Casarsa. His first theatrical drama ‘The Turcs tal Friûl / The Turks in Friuli’ (1944) was written in Friulan. During WWII when regional Italian dialects were being suppressed Pasolini set up the ‘Academiuta de lenga furlana / Little Academy of Friulian Language‘ with the help of his mother Susanna, and it is in her home where the study centre is today.

Pasolini had no ancestral claim to Friuli-Venzia Gulia, and yet adopted the language as his own tentative hybrid form of cultural expression – ‘a minority language he did not speak but learned as a sort of mystic act of love, a kind of félibrisme like the Provencal poets’. His earlier childhood at his birthplace in Bologna, on the other hand, was far from idylic. His father was a military man and strong Mussolini defender who Pasolini had a difficult relationship with. Amongst Pasolini’s critique of institutions is his disbelief in the institution of the family. Stemming from personal experience he saw it as just another artificial system of control and authority.

The history of Friuli is also not without its difficulties. The etymology of Pasolini’s resting place in Casarsa stems from ‘casa’ (home) and ‘burnt’ (arsa) or ‘burnt house’ meaning there was likely a historic devastation there at one point. The year following Pasolini’s horrific death in 1975 the Friuli region was the victim of a massive earthquake which devastated the region for years, leaving 978 dead and 157,000 homeless. Amongst the extensive rehabilitation work to rehouse it’s citizens was the task of reconstructing it’s architectural history, sometimes involving the rebuilding of entire medieval villages such as the walled village of Venzone. This lends a theatrical aesthetic in parts which merely adds to the regions supernatural atmosphere.

Perhaps Friuli was Pasolini’s ‘Avalon’ as much as St. Francis’ dream of a world of perfect harmony and love is merely a beautiful idea. In Pasolini’s Franciscan/Marxist homage ‘The Hawks and The Sparrows’ (1966) the birds are eventually converted to religion but one group disagrees with the other and attacks them. As in reality a world without conflict and tragedy only exists in the fictional realm. I believe what Pasolini saw in Friuli-Venezia Gulia was a very real environment whose differences and conflicts merely strengthened its legendary regenerative spirit.